A couple of months ago, I diverged a bit from the light chatter you’ve come to expect here at Twice Cooked to promote a cause — Kiva.org. I contended, as I recall, that as long as I have this tiny soapbox of a web site, and as long as I have (at least some) regular visitors, I might as well use that meager position to do something good. And Kiva — and microlending — are certainly that.

Well, today I come to you with another cause, and a similar soapbox rationale. This time, it’s not helping local entrepreneurs in developing countries get their projects off the ground. Instead, it’s helping creative professionals around the world take control of how people use, reuse, repurpose, and revise their work.

That’s right, folks. Today’s cause: Creative Commons.

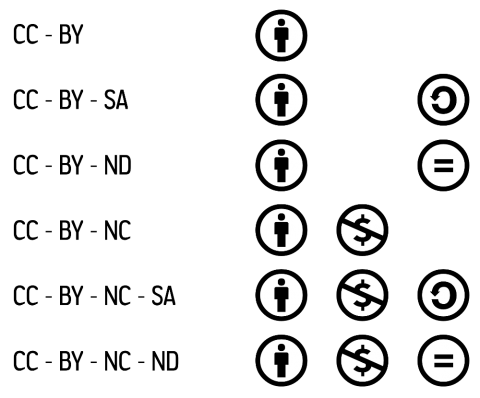

For those who don’t know, Creative Commons is, in their own words, a nonprofit organization that enables the sharing and use of creativity and knowledge through free legal tools. They provide the legal language for a set of basically mix-and-match licenses that allow you, as a producer of creative content, to offer the public permission to share and use your creative work — on conditions of your choice. What Creative Commons licenses do, in other words, is supplement and specify traditional “all rights reserved” copyright by allowing artists to control which rights they want to hold on to and which they don’t, allowing a legally clear path for their work to be shared, remixed, or redistributed on their terms.

It sounds arcane, but it’s really not. All of the content here at Twice Cooked, to offer you an illustrative example, is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA license. That means that I allow visitors to Twice Cooked the option of copying, redistributing, and remixing my content under three conditions: 1) that I am acknowledged as the original author; 2) that folks not use it for commercial purposes; and 3) that any modifications continue to be distributed under the same licensing conditions.

As far as restrictions go, this falls somewhere in the middle of the Creative Commons licensing spectrum (you can find an explanation of the full range here). They offer licenses as permissive as only requiring that your work be attributed (CC BY). And they offer licenses as restrictive as requiring that your work not be modified in any way (CC BY-NC-ND).

It seems to me that a licensing scheme like this is good for a couple of reasons. In practical terms, it means that rather than creating an adversarial relationship between authors and audiences — one in which each side is left to fight for the right to control the work — it creates a collaborative relationship — one in which the author is acknowledged as the creator of a given work, but in which audiences aren’t assumed to be passive participants, consumers who are expected to read and absorb information without any means to respond to and improve on it. It’s well established in academia that the creator-audience relationship is an active one. And Creative Commons gives that fact some standing in law.

More broadly — and this point may in fact be arcane — the existence of Creative Commons denaturalizes the idea of copyright, and the dichotomy between copyright and public domain. We tend to assume that copyright is just the way things are: that creators make something, and then they have rights to it for x amount of time (the life of the author + 70 years in the U.S.). But that system is a product of historical circumstances. It is a product of the basically industrial capitalist notion that ideas are products like widgets and sprockets, and that in order for them to be worth something, they must be monetized, packaged, and sold for profit. And it is the product of a basically classist notion that ideas of substance are invented by people of standing, and that those ideas must be legally distinct from the intellectual rabble who have nothing but a stew-pot of traditions that have filtered down to them from the geniuses of generations past (the public domain).

Now, I’m not saying that the creators of content shouldn’t have the right to control the things that they’ve made. And Creative Commons licenses don’t say that either. What I’m saying is that there are lots of different possible schema out there for how intellectual property could work, and that Creative Commons makes us ask the questions: why have we chosen the one we have? And what are the consequences of that choice for encouraging or stifling new creativity?

As with my post about Kiva, I am (obviously) not going to try to hard-sell you into supporting Creative Commons. If it’s not a cause that interests you, or if you believe in the exclusivity of “all rights reserved” copyright, then feel free to give it a pass.

If you are interested, however, there are a couple of things you can do: you can click here to offer a straight-up donation to Creative Commons — to help keep them up and running and doing their good work; or — if you’re like me and like geeky swag — you can click here to support them by buying super-cool Creative Commons merchandise, including this t-shirt, designed by Randall Munroe of XKCD.

* The first and second image in this post are via http://www.adiffuser.net/. The third is from the Creative Commons web site.